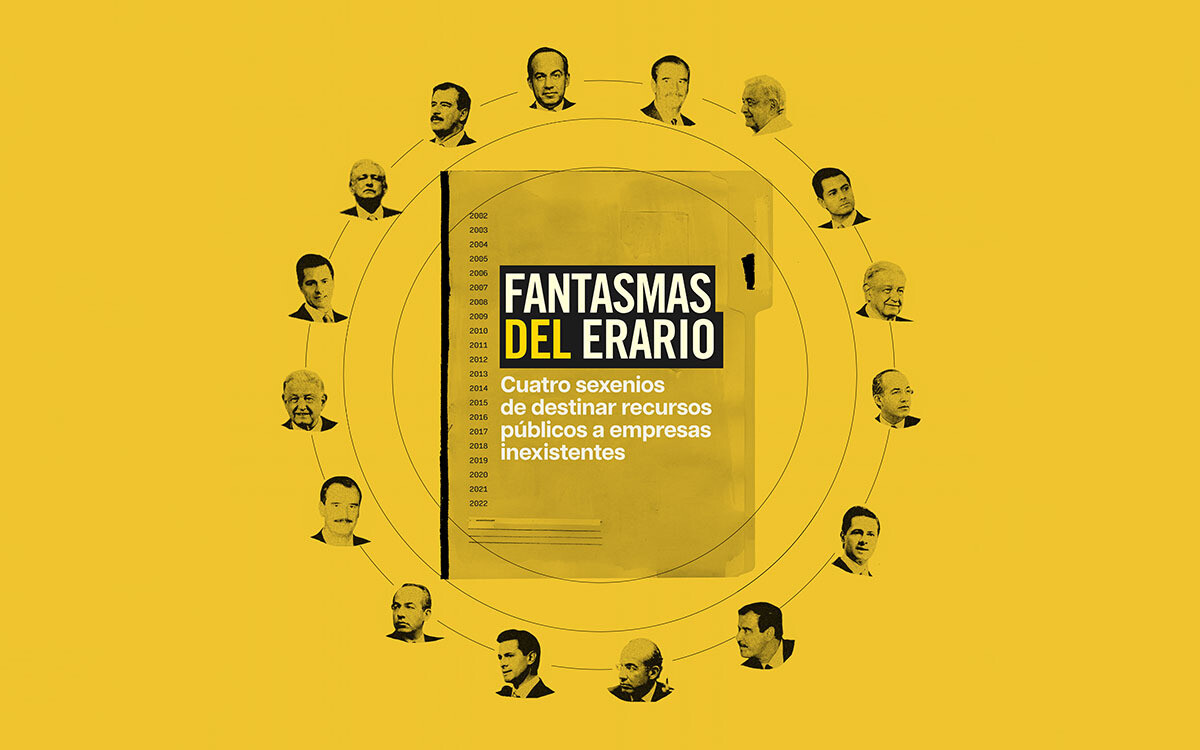

During the last four six-year terms, the Mexican government has granted more than 11,492 million pesos in federal contracts to companies involved in simulated operations (EFOS), also known as ghost companies, fronts, non-existent, or invoicing firms. These are companies that lacked the operational capacity or resources to fulfill the services offered. Despite the anti-corruption rhetoric, during Andrés Manuel López Obrador's administration, contracts continued to be awarded to these non-existent firms, and the identification of these companies by the SAT decreased.

Between 2002 and 2022, 3,529 contracts were signed with 834 EFOS in the federal public administration, which operated on average for 8.1 years until discovered. A review was conducted on 87 EFOS selected for their larger amount of money and contracts, or for being contracted when it was already known they were definitive companies. It was found that of the 7,400 million pesos represented in this sample, only a quarter (1,241 million) had evidence of compliance.

During Felipe Calderón's administration, these companies received the largest amount of federal money. However, the first records of contracts with ghost companies date back to Vicente Fox's presidency. This situation has represented two decades of public money contracts assigned to non-existent companies, marking one of the largest transfers of public resources in recent Mexican history.

Over the years, these ghost companies have infiltrated public contracting procedures in Mexico, obtaining millions from the treasury and directly affecting society with simulations of services or works, execution of faulty projects, or overpriced bids. Almost half of the money intended for these companies should have been used for essential infrastructures like roads, schools, medical equipment, potable water networks, among others; however, in many cases, the realization of works or services was not evidenced.

Quinto Elemento Lab made a request for invoices and proof from a sample of 1,311 contracts to verify if the contracted services were actually delivered, discovering that ten ghost companies concentrated almost half of the public resources allocated to EFOS. Over 20 years, these companies received large sums of public resources daily, while the SAT ceased to collect 7,239 million pesos in taxes from these same companies due to waivers or cancellations of tax debts.

This investigation reveals how the federal government has maintained a constant relationship with EFOS over the last two decades. The distribution of money was not equitable; some companies amassed large sums through few contracts while others secured many small agreements. Some institutions like CFE, SCT, IMSS, and ISSSTE concentrated a significant portion of the money delivered to ghost companies.

In summary, it highlights a contracting system that allowed the participation of front companies for two decades, with few sanctions and complaints, indicating a trans-generational phenomenon with public consequences.