The Mexican War of Independence did not begin as a spontaneous uprising, but as a broad social movement involving various segments of society. From educated creoles and military leaders to indigenous peoples, peasants, artisans, and women who played a crucial role in logistics, each formed a social mosaic without which the struggle for independence would not have gained the momentum it did in its first months.

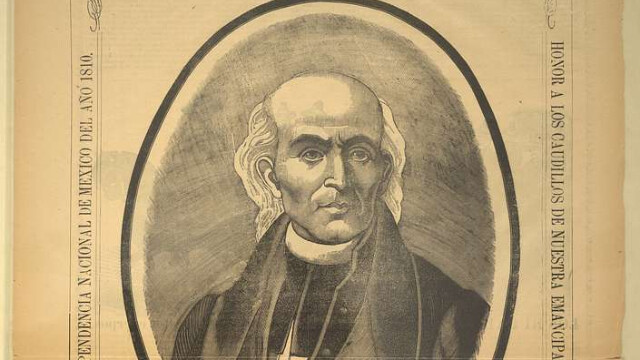

Hidalgo's Inner Circle The first to respond to the call were Hidalgo's closest circle: enlightened creoles and insurgent leaders. The independence movement was not improvised. Key figures like Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, and Mariano Abasolo provided discipline, strategic knowledge, and leadership. Their participation was vital as they gave the movement its structure.

The Role of Peasants and Indigenous Peoples Peasants and indigenous peoples, who had suffered for centuries from injustice, exploitation, and high taxes, saw in Hidalgo's uprising an opportunity to seek justice and dignity. Many joined, armed only with work tools—machetes, sticks, makeshift spears—demonstrating their complete willingness to fight. Their involvement not only significantly increased the ranks of the insurgent forces but also provided an emotional core, transforming the rebellion into a popular cause.

Artisans and Urban Workers Artisans, such as carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, bakers, and weavers, also answered the call. Their skills were invaluable: they could manufacture rudimentary weapons, repair tools, and assist in building fortifications. For them, the insurgency was a chance to challenge the economic restrictions of the era, especially monopolies and trade barriers.

Women in the Independence Movement Women's participation was not limited to the figure of Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez. They played decisive roles as messengers, guides, suppliers of food, nurses, and clandestine organizers. Figures like Maria Manuela Herrera, Maria Luisa Martinez, and Gertrudis Bocanegra contributed to logistics and support. Their involvement proves that the movement was a collective effort where men and women took equal risks.

Deserters and Secret Supporters Some soldiers from the colonial army deserted to join the insurgents, bringing with them military experience. While thousands openly joined the movement, others, particularly large landowners (hacendados), supported it clandestinely by providing horses, weapons, food, and shelter, risking their properties and lives.

Religious Symbolism and Uniting Forces Hidalgo's call was understood not just as a political invitation but as a religious act filled with legitimacy and hope. He carried the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a deeply rooted symbol among the popular classes. This spiritual dimension transformed the insurgency from a mere rebellion into a sacred cause, fought for divine protection and the chance to change their lives and those of their families.

The Growth of the Movement and Its Impact In the days following the "Cry of Dolores," Hidalgo's army grew exponentially with each town he visited. At its peak in the first months, the insurgent forces numbered between 40,000 and 80,000 people—an unprecedented mobilization for the time. This caused fear among colonial authorities, forced Spanish military strategies to change, and led to increased surveillance of sympathizers.

Conclusion The call to arms issued by Father Miguel Hidalgo was answered by a diverse range of people, each driven by their own motives but united by a common desire: to transform an oppressive reality and build a more just society. The movement's success lay in its social diversity. Educated creoles provided direction and strategy, indigenous peoples and peasants offered mass numbers and local knowledge, artisans contributed technical skills, and women handled logistics and support. Without the contribution of each of these groups, the Mexican War of Independence could not have become one of the most significant events of the 19th century and forever change the nation's destiny.